If you are interested in pointed pen calligraphy, you have certainly heard more than one eminent calligrapher state their opinion about the right way to call the various pointed pen styles popular today…

The term “Copperplate” is on all the book covers, but it is often pointed out that it may actually be inappropriate. Frankly, I found many attempts of explaining this issue quite confusing, so for my very first post on this blog I wanted to find the answer to this burning question :

“What is the name of the calligraphy style I like to do ? ? ?”

According to Dr Joe Vitolo, Copperplate “has become the term used in modern day calligraphy circles for an entire range of shaded scripts1https://www.iampeth.com/lesson/script-copperplate-style-engrosser%E2%80%99s-script” derived from an 18th century style called English Round Hand. To go further, some modern definitions – including Wikipedia’s – state that “Copperplate” refers to all pointed pen calligraphy styles… But what exactly are these styles ?

Before I try to answer this, I’d like to explain why the term was chosen to name a writing style in the first place : what does “Copperplate” mean originally and why has its meaning evolved ?

From the Calligrapher to the Engraver

The Oxford English Dictionary tells us that the first meaning of Copper-plate is of course “a plate of copper”, on which an illustration can be “engraved or etched for printing”. This method allowed the reproduction of very fine lines and complex illustrations that, once printed, also came to be referred to as “copperplates”.

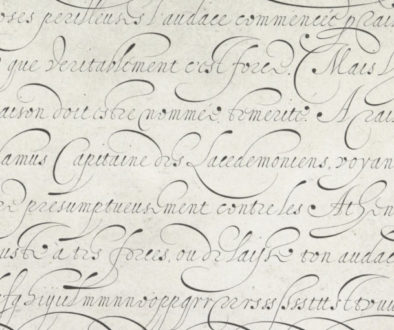

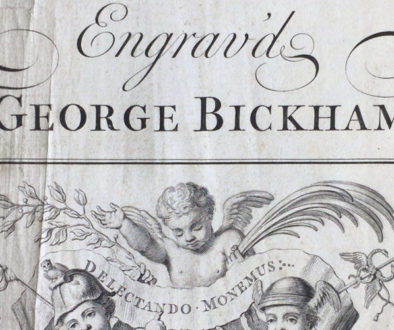

In the early 1700’s, English scribes designed a new handwriting style that they called the Round Hand and flooded the market with copy-books printed from copperplates, displaying the new fashionable hand. The most famous of these books is George Bickham’s Universal Penman (1733-1741).

The Round hand was meant to be written in a continuous movement : it was fast, the letterforms were simply built, they were legible even when they were badly executed… : it was a perfect writing style for “merchants and businessmen”, and it was adopted as such by all the writing teachers in the country.

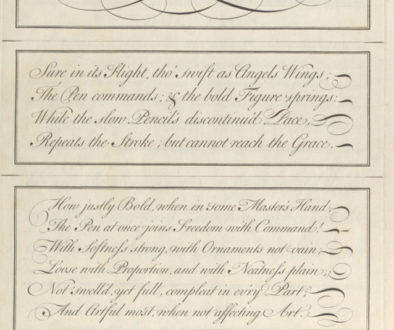

However, the first generation of penmen who developed the Round Hand were concerned that their engravers were not able to fully render the natural strokes of the pen, as well as the simple and subtly imperfect gracefulness of their written exemplars. Indeed, engraving letterforms on a copper plate can’t be done as naturally as writing. Even though most engravers did a beautiful job, they still admitted that the printed plates were inferior to the written exemplars because they lacked spontaneity (but they were still really accurate in terms of forms).

From the Engraver to the Calligrapher

The downside to this was that, by the second half of the 18th century, calligraphers who had learned to perfect their hands by copying these plates developed a taste for very polished letterforms. They were tempted to slow down and carefully draw their strokes one by one, rather than write in “swift movements”. The Round Hand letterforms published by these master calligraphers became sharper, thinner, slender, some might say more graceful… But they lost the lively, natural aspect of handwritten letters.

Around the end of the 18th century, another change impacted the whole aspect of the Round Hand shown in copybooks : penmen were starting to discard the traditional broad cut quills for the more versatile pointed cut quill… Instead of having to change pen when they wanted to change the size of their script, they just had to adjust the pressure on the tip of the pen to open it to their liking. This allowed them to make super thin hairlines but their shades were often less “dramatic”. When the steel pen was finally manufactured, pointed nibs became the norm for most people2See this post to know more about the transition from broad quill to pointed steel nib.

However, any beginning student of Copperplate knows that handling such a pen is not as easy as it looks… and people didn’t all have the time to learn how to write beautifully. The quality of handwriting in the 19th century was impacted and harshly criticized (In the UK, the stronger critics were expressed by the Arts & Craft movement).

The meaning of the word Copperplate

By the early 19th century, the word Copperplate was used to refer to a “style of careful handwriting”3The earliest examples of such use of the word cited by the Oxford English Dictionary date from the 1820’s… In other words, a handwriting style so well executed that it looks like a copperplate print.

I’d like to point out that this definition does not mention a calligraphy style (calligraphy being writing as an art form), yet we saw earlier that there were calligraphers at the time, pursuing the art of writing as perfectly as possible for the sake of producing beautiful artworks. These people still referred to their writing style as Round Hand, sometimes “Ornamental Penmanship”. In their hands, the style kept evolving and new techniques based on the old script were adopted (Movement Writing, and Engrosser’s Script come to mind).

So why did calligraphers stop using the original name of the script ?

I think that one of the probable reasons is that “Round Hand” was a very generic way to call a writing style after the Renaissance. The French had their “Ronde”, the Spanish their “Redondilla”, the English called the Italian hand “Round Hand”, then they called the French’s Bastard Italian “A-la-mode Round Hand”, before coming up with the “English Round Hand”, later styles also got the same unoriginal names, which made it pretty confusing.

Then, in the early 20th century Edward Johnston41872-1944. A British calligrapher who had been influenced by the Arts & Craft Movement, credited as the man responsible for the revival of traditional calligraphy in the early 20th century. came up with his “Foundational hand”, which was also referred to as “Roundhand”.

As the British Round Hand had been dethroned by this new “Round Hand”, “Copperplate” became its new name. But Johnston and his followers also (mis-)used the term as a way to show that the old Round Hand was not a proper calligraphy hand.

They saw the name “copperplate” as a proof that the Round Hand was a degenerate handwriting style, derived from engraved plates rather than original handwritten designs. Because of their views, the name “Copperplate” actually seems to have had an almost pejorative meaning among calligraphers during the biggest part of the 20th century. This doesn’t mean that this kind of script wasn’t appreciated at all, many calligraphers and historians conceded that it had its charms, but they always treated it as a decadent style that did not have its place in the pantheon of calligraphic hands.

As a result, very few specialists actually looked into the actual history of the English Round Hand – or its technique – and our generation is left with scarcely any valuable information. For one thing, there is this confusion about the way we should call the various scripts sharing the name Copperplate, or even the common inability to identify these scripts as being different.

Meet the Copperplate family

Calligraphers generally agree that Copperplate is written with a pointed, flexible nib. Historically, this kind of writing included ornamental variations – used by calligraphers, engravers, letterers, artists – and handwriting systems used to teach how to write. Both kinds of writing coexisted, but the ornamental variations were typically more flourished and included a wider number of letterform variations.

The various hands in the Copperplate family are : English Round Hand and its sub-styles called Round Text, Round Hand and Running Hand, (I’m including Italian Hand here as well)5I wrote a post describing these various hands here, Spencerian and its variations (Ornamental Penmanship and Business Penmanship), Engrosser’s Script / Engraver’s Script / American Roundhand, Modern Calligraphy and all of their respective variations… It’s a big family, and I probably forgot some of its members, but they all have common roots.

In my opinion, as long as we know what we’re talking about, there is certainly no harm in using this widely accepted appellation for all pointed pen styles. But because it encompasses many different hands, using it is like calling all medieval broad pen hands “Gothic”…

While calligraphy newbies may not have the knowledge to differentiate all of these styles, the advanced calligrapher should probably know the difference and be able to use the proper names as long as it is not too confusing.

After all, the popular Madarasz advised us to “know what we want to execute”, don’t you think it includes knowing about the calligraphy styles that we aspire to excel at ?

__________________________________

Peter Gilderdale wrote a very interesting article on this subject (1999). You can read it here.