We left the 17th century with the works of English Writing Masters like John Ayres, who had been seduced by the clean and simple characteristics of the French and Dutch “round hands”, based on the oval shape and derived from the Italian Bastard seen in Materot’s copybook of 1608. These round hands were very practical : simple to teach and learn, faster to execute, they allowed for some ornamentation and were very legible. All of those qualities made such hands ideally suited for the needs of commerce, which the British Empire’s power relied on, but none of the existing modern writing styles were actually British. The Writing Masters in London saw this as an opportunity to better their status in society : by developing a national hand suitable for the booming commercial activity in the Empire, they thought they would contribute to the expansion of the British culture and hoped to gain more respect.

By slightly adapting the existing round hands to their own standards, the new generation of writing masters championed by John Clark, George Shelley and Charles Snell, with the help of their favorite engraver, George Bickham, managed to develop the new English Round Hand. The extreme rivalry between these masters led them to innovate and publish many copybooks, allowing the new “natural writing” to spread and eventually replace some of the old, obsolete hands in Great Britain. But the simplification of the writing style made learning to write easier (people only needed to learn the “easier” Round Hand instead of “all the hands”), and writing became a practical skill more than an artistic skill. The social standing of writing “teachers” did not improve as they had hoped… But their creation, the English Round Hand continued to spread out of the borders of the Empire into the main European countries ; even in France, where pieces of the British culture were generally not welcome, the Round Hand eventually replaced the Batarde and the more expeditive Coulée.

Historians of calligraphy generally consider that calligraphy ceased to exist in the 18th century1About this, my post on the use of the name Copperplate migh interest you, they neglected the history of the English Round Hand because in their opinion it was just a “handwriting system”. This is only partially true : as writing became more accessible to the masses, thanks to the simplification of the styles in use, calligraphers (or professional scribes) lost their monopoly over the use of writing, but they retained their role as experts in the Art of writing. You see, copybooks and specimens of fine writing never stopped being collected by amateurs of the art, even though tastes and fashions changed over time, even though writing had to become “simpler” and accessible to everyone, beautiful writing remained an object of fascination and passion for some artists…

The copybooks listed below reflect this evolution : the writing styles illustrated gradually became simpler and adopted a uniform “generic” look to suit the needs of clerks. but judging by the number of copies published and sold, fine writing was not a dying art. Unfortunately many books aren’t freely available online, know that this is only the tip of the iceberg.

If you want to know more about copybooks in general, Paul Antonio shared his knowledge about them in this video.

England

SHELLEY (George) & SEDDON (John), The Penman’s Magazine, 1705. (Google books backup / Newberry)

George Shelley is one of the masters whose work played a major role in the development of the Round Hand, this was his first publication. The book is a combination of his own beautiful writing combined with the pen-flourished adornments of John Seddon, who had died in 1700, leaving his unpublished original ornaments in the hands of Shelley.

SHELLEY (George), Alphabets in all the hands…, 1710. (Google books backup)

This book was published a few months after Shelley was appointed Master to the writing school at Christ’s Hospital (the most renowned writing school in London at the time), an event the provoked a bitter quarrel between him and other writing masters. This copybook was done for the use of the writing school and includes models of full alphabets in the most useful hands at the time.

BICKHAM (George), Round Text, a new coppy-book…, 1712. (Google books backup)

George Bickham is a major figure in the history of the English Round Hand, but his position as an engraver of calligraphy was much higher than as a practitioner of the art. He engraved the great majority of the best copybooks published between 1710 and 1750. Bickham dedicated this book to his master, John Sturt (who was himself the best letter engraver of his generation). The plates show models of a hand that already bears most of the features of the “classic” Round Hand as we can see it in his major collection of penmanship, The Universal Penman (1733-1741).

SNELL (Charles), The art of writing in its theory and practice, 1712.

We have already encountered Snell in 1694 with his Penman’s Treasury Open’d. He took over John Seddon’s place as the master of Free Writing School in 1700, and instructed some of the best penmen of the next generation, the most famous one being Joseph Champion. This second publication was a copybook meant for his students. In its pages Snell harshly criticized George Shelley (without naming him) for using too many unnecessary ornamentation, and proceeded to set up a standard of rigid formality in writing. In 1714, he even published a complete set of rules presenting the formation and proportion of each letter… criticizing the work of another major figure in the world of penmanship : John Clark. It is interesting to note that all the books published by these rival masters were engraved by George Bickham…

SHELLEY (George), The Second part of Natural Writing, 1714.

Natural Writing is Shelley’s major copybook. The first part of the book was published around 1710 and was very successful (one page here), which irritated Snell who was offended by some overly flourished pages. Due to his popularity, Shelley was a busy man… the publication of the second part of the book was delayed until 1714, even though some subscribers had already paid their copy when the book had been announced. This copy includes a beautiful plate showing the various angles at which the quill should be cut for each of the major hands. The long introduction is also intersting if you want to know more about the “techniques” used at the time. Shelley’s execution of the Round hand was really beautiful, a point on which both Clark and Snell approved. Unfortunately, Shelley ended up losing his position at Christ’s Hospital and died in low circumstances around 1736.

RAYNER (John), The Paul’s Scholar’s copy book, 1716. (Google books backup)

Rayner was a student of John Ayres’ and was a teacher at the same school as his mentor : Saint Paul’s. The influence of Shelley’s ornaments is also visible in this book.

SYMPSON (Samuel), A new book of Cyphers … wherein the whole alphabet…, 1726. (British Library, unavailable since the hack in October 23)

A book of monograms.

BICKHAM (George), Youth’s Instructor in the Art of Numbers. A new cyphering book…, 1730. (Google books backup)

Many Writing Masters were also teachers of arithmetics and / or accountants, and some published manuals about this subject as well as copybooks. This manual is different from most of such publications because the pages were written in the Round Hand, with some really beautiful titles. Bickham was primarily an engraver, not a teacher… He probably made this book because he knew his usual clients (writing masters, students and collectors of calligraphy) would certainly appreciate it.

ANON, The Young clerk’s assistant, or penmanship made easy…, 1733. (Google books update)

This book is sometimes attributed to Bickham who engraved it for Richard Ware, who was a publisher. It includes a beautiful alphabet of capitals.

BICKHAM (George), The Universal Penman, 1733-1741. (alternative link / Google books backup)

This is Bickham’s best known copybook. It was issued in 52 parts between 1733 and 1741 and included the works of all the best penmen alive at the time. This is a major reference filled with many examples of capital variations in Round Hand and Italian hand. A fac-simile by Dover is also available for a very reasonable price.

Album of trade cards and invitations, between 1733 and 1769.

You wont find instructions about writing here, but you’ll get a glimpse into the daily work of writing masters and engravers in 18th century England… This is a collection of trade cards engraved for a wide variety of London businesses. Click on the image to see the whole collection.

RICHARDS (William), The Compleat Penman, 1738.

This book is a compilation of multiple penmen’s works, like the Universal Penman, except it wasn’t engraved by Bickham.

This link will take you to a video of Paul Antonio showing the pages and sharing his knowledge of what copybooks were and how they were used.

LEEKEY (William), Discourse on the use of the pen…, 1744.

The only examples of Leekey’s penmanship are in the early pages of the Universal Penman. In 1744 he published this pamphlet which consisted of observations on writing in general and directions on posture, technique, and on the way to cut a pen. His views on the proper posture for writing were different from the accepted practices of the day as he advocated writing on a flat table instead of upon a sloping desk. He also advised to incline the paper to the left. The whole book was printed in letterpress, no plates were included.

BICKHAM (George), The British Monarchy, or a chorographical description…, 1748.

This is not strictly speaking a copybook, but a description of all the “dominions subject to the King of Geat Britain”. However, it contains typical models of the Round Hands.

BICKHAM (George), The Drawing and Writing Tutor, 1748.

This book contains illustrated instructions about drawing and some basic examples of the Round Hand.

CHAMPION (Joseph), The Parallel or Comparative Penmanship, 1750.

In this book, Joseph Champion wants to show how English penmanship has brought significant improvement in the art of writing, through the development of the standardised English round hand (and its variants). The engraver copied selected older models from renowned master like Materot, Barbedor, Velde, Perling… which Champion admires, and the calligrapher reinterpreted these pages, making a sort of ‘modern, improved copy’. We can see both the old and new together and get an understanding of the evolution of handwriting after the Renaissance. It is in my opinion Champion’s masterpiece.

CHINNERY (William), Writing and Drawing made easy…, 1750.

Chinnery developed his talent for fine writing while working as a bookseller, then he became a celebrated “writing master and accountant”. This is his only copybook, a very peculiar publication : Chinnery illustrated each letter of the alphabet with an engraving and a moral copy featuring an animal.

CHAMPION (Joseph), New and complete alphabets…, 1754. (Google books backup)

Joseph Champion was Charles Snell’s apprentice. He set up his own writing school in 1731, and it wasn’t long until his talent caught the eye of George Bickham who commissioned him to write 47 plates for the Universal Penman. “New and Complete Alphabets” is exactly what the title says : it contains models of alphabets in all the hands useful to scribes.

CHAMPION (Joseph) and BLAND (John), Penmanship illustrated…, 1759. (Google Books)

Bland was Snell’s apprentice as well, and his penmanship was as celebrated as Champion’s, but he only contributed 5 plates to the Universal Penman. This book contains models of various bills, alphabets, layouts and phrases meant to be copied as practice. The main hands taught here are Round Text, Round Hand and Running hand.

CHAMPION (Joseph Jr), Penmanship or the art of writing, 1770. (Google Books)

This manual published by Joseph Champion’s son does not contain models of penmanship. It consists of “directions for holding the pen, the position of the body (…), how to make pens (…), and some general instructions for the better attaining of Ornamental Writing.”

RUSSELL (John), A complete and useful book of cyphers…, 1775. (Google Books)

A book of monograms.

SERLE (Ambrose), The art of writing, 1776.

Not a copybook, because it doesn’t contain any examples… but an externsive discourse on the theory of writing, with mathematical projections and so on.

TOMKINS (Thomas), The beauties of Writing, 1777. (Second link, in color)

Tomkins was a highly praised penman in his time, some commentators saying that he had “attained the highest eminence in his art”. However, he had to live with the bitter disappointment of being denied the place he desired at the Academy of Arts. Historians of penmanship like Stanley Morison and Ambrose Heal certainly did not care for Tomkins’ work, judging that it wouldn’t have been good enough to be featured in Bickham’s Universal Penman… Tomkin’s style was different from the “classical Round Hand”, mainly because he seems to have used a pointier, finer pen, which made the contrast between very thin hairlines and thick downstrokes more dramatic. Some sources mention that around 1780, the pointed flexible pens that had been used for “command of hand” until then were now being used to write as well. Historians of calligraphy usually regret that this change brought about the end of beautiful penmanship and the deterioration of the overall quality of handwriting. It is true that from this point on, professional penmen would either follow a path of simplification (leading towards handwriting systems) or a path of artistic or ornamental writing (“calligraphy” used in title pages, official documents, certificates…).

BROWNE (Samuel), General Rules to be observed in writing the Round-hands, 1778. (Google Books)

This book includes very useful guidelines about the Round Hand like how to space words and letters…

BUTTERWORTH (Edmund), Butterworth’s Universal Penman or the beauties of writing…, 1785. (extract)

Edmund Butterworth was a writing master in Endinburgh, where he also published and sold copybooks. This Universal Penman is not a collection of various penmen’s works as it only displays Butterworth’s work (sentences to copy and various layouts and flourishes). His style is similar to Tomkin’s.

TOMKINS (Thomas), New large text and Dutch striking alphabets : with a variety of examples in the hands most approved for business, 1785.

This copybook is much less ornamental than the previous one, it contains some basic models of words, phrases and texts, as well as beautiful examplar of capitals.

THOMSON (William), The writing master’s assistant, 1786.

These are just 3 pages of the book. Thomson’s exemplars seem to have been popular with some French masters who copied them to the best of their abilities (Saintomer published a book called “Copies d’après Thomson” c.1800)…

The models are pretty standard for English Roundhand at the time.

LANGFORD (Richard), A complete set of rules and examples for writing with accuracy & freedom, 1787. (color copy)

Robert Langford was a respected writing teacher whose “copy slips” were reprinted many times after his death in 1814. This is one of his best known publications, where he explains the rules of the round hand.

LANGFORD (Robert), A copybook of capitals, 1793. (color copy)

This booklet contains a set of elegant capitals in the round hand.

ROBERTS (P), The Writing Master’s Assistant, 1794.

The copy available online isn’t great, but it contains a nice alphabet of capitals and many aphorisms to copy…

MILNS (William), The Penman’s Repository, 1795.

This is Miln’s only copybook, it contains a set of various alphabets and a few beautiful layouts. Dover published a fac-simile of this book with Tomkins’ Beauties of writing in 1983, some copies can still be found in used books stores.

WEBB (Joseph), Webb’s useful penmanship : being the last work of this kind, 1796.

This is a very simple looking copybook, in the style typical of the end of the 18th century. The penmanship is much more “practical” than “ornamental”, but the calligraphy is still beautiful in its simplicity. The models include longer texts and sober layouts.

LANGFORD (Robert), The beauties of Penmanship illustrated in a variety of examples…, 1797.

Langford’s largest copybook, inspired by the works of Tomkins and Champion.

WILLIAMSON (Richard), Williamson’s Penmanship for the use of schools, 1797. (Google Books)

The copy seems incomplete.

SMITH (Duncan), The Academical Instructor : A New Copy Book Containing Alphabets, 1799.

Unfortunately Google’s copy is not very legible, but the book contains mainly short sentences in round hand and running hand, each starting with a different capital.

France

HELWIG (Joseph), Exemples d’ecriture françoise, ecrits et gravé par Joseph Helwig, c.1700. (added July 2020)

This is a very simple copybook, with very little ornamentation. Only the French Ronde is illustrated.

(CHIQUET ?), Nouveau Livre d’Ecriture présentement en usage, avec des principes et règles…, 1707.

DUVAL (Nicolas), Pratique universelle des sciences les plus nécessaires dans le commerce et la vie civile…, 1725. (alt.copy)

We have encountered Duval in the previous century with a copybook that mainly included plates of examples for the 3 French hands : the Ronde, the Batarde and the Coulée. This manual contains much more information on an array of subjects useful for tradesmen. Duval explains how to write, how to choose which hand to write according to the type of document, how to tackle layouts for a variety of documents, how to formulate letters… as well as instructions about arithmetics and accounting. Of course, the plates illustrating the part about writing are less oriented towards decorative penmanship : according to Stanley Morison, this is the best book illustrating the styles used at the time, and the way these styles were actually used. If the copy form Gallica is still unavailable when you read this, there is a microform version hosted by Google here.

ROYLLET [ROILLET] (Sébastien), Présentation des feuilles d’écriture française du XVIIIe siècle…, 1728. (extract)

Sébastien Royllet had a special talent for calligraphy and learnt most of his art by himself : his master in the art was so impressed with his pupil that he eventually took lessons from him and later boasted about having been one of Royllet’s first students… Unfortunately the publication was not digitized in its entirety, only one page can be seen.

ROYLLET [ROILLET] (Sébastien), Les nouveaux principes de l’art d’écrire…, 1731. (alternate copy at the Bibliothèque de Paris)

This is Royllet’s most important publication, a complete course on writing in the form of questions and answers (with illustrations), describing each of the lowercase letters as well as useful things about technique (how to cut a pen, how to hold it, the movements to do with the arm and fingers…). The last part of the book shows that Royllet was very analytical in his approach, some of his detractors made fun of him saying that one had to be anatomist and geometrician to understand his book. Very few of his colleagues appreciated Royllet, who had become known for his “original” views on the art of writing that called into question some of the old principles everyone agreed on. But Royllet’s talent was recognized by the most respected “maitre écrivain” of the time, Louis Rossignol, who was even his teacher for a time. Together, these two masters managed to perfect the French art of writing, giving a more elegant and majestic look to the three French hands.

ROSSIGNOL (Louis), L’art d’écrire Nouvellement mis au jour…, 1741. (Alternative link : better images)

Louis Rossignol was a little older than Royllet, but just as talented and much more liked and respected by his peers. He was instructed in the art of writing by Olivier-François Sauvage, the most reputable teacher of the time (who didn’t publish any copybook), but was prematurely expelled from his school for having copied his master’s works so succesfully that Sauvage didn’t even see the difference… Rossignol is one of the masters who invented and perfected the “Coulée” script (a cursive hybrid of the Ronde and Batarde). He didn’t publish any copybook while he was alive, this book was composed using Rossignol’s works, unfortunately the engraver was not as subtle with his tool as Rossignol was with his pen.

after ROSSIGNOL, Nouveau Livre d’Ecriture D’apres les plus belles Pieces de ROSSIGNOL Pour l’Instruction de la Jeunesse et la Satisfaction des Curieux, 1744.

The “famous” French master Louis Rossignol never had any of his work engraved, according to Charles Paillasson, who was one of his students. However, two books bearing his name were published after his death. This is the second one, engraved by Hyacinthe Aubin. (more info, in French, here)

ROSSIGNOL (Louis), PECQUET (Pierre), Traité d’Écriture de Rossignol, (c. 1792-1803).

Louis Rossignol (1694-1739) was the most admired French writing master of the 18th century, but he never published his work. Several books came out after his death, engraved from the manuscripts that were collected by his numerous admirers. of course, they weren’t all of good quality and didn’t only contain pages executed by the master… This is one of those books. The plates included here are destined to guide the beginner in his learning of the Ronde, the Bâtarde and the Coulée. Two plates are signe “Pecquet”, the author was probably the writing master Pierre Pecquet, who was active as a writing master after Rossignol’s death (1755- c. 1784). (more info, in French, here)

GLACHANT (François Michel), Nouveau traité d’écriture enrichi de plusieurs pièces gravées d’après le chef d’œuvre de M. Rossignol, 1742.

This is another posthumous publication of Rossignol’s work, where the engraver was better at rendering the subtelty of Rossignol’s pen.

ANON, L’art d’écrire contenant une collection des meilleurs exemples d’après Messieurs Rossignol & Roland…,1756. (alt. copy)

A third posthumous book of Rossignol’s works, collected with the work of another respected master : André-François Roland

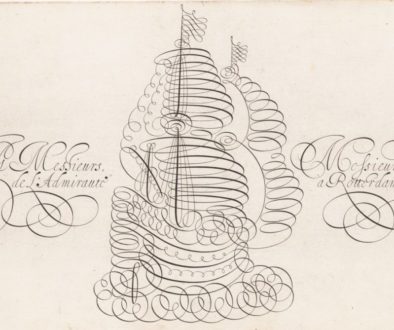

ROLAND (André-François), Le grand art d’écrire…, 1758. (extract)

Roland was one of Rossignol’s pupils. His flourishes were often better executed than the calligraphy itself, which impressed the public and gave him a good reputation, but his ability with the quill did not match his master’s.

ROLAND (André-François), Recueil de modèles de calligraphie gravé et publié par Le Parmentier, date unknown.

Copybook engraved after originals by Roland (not published by Roland himself).

Nouveau livre d’ecriture italienne batarde très utile aux Commercans, 1758.

D’AUTREPE (Jean-Etienne), Traité sur les principes de l’art d’écrire et ceux de l’écriture, c.1759. (alt.copy)

D’Atrèpe is considered one of the most learned calligraphers of this era. This is his major publication. Like many other treatise on the art of writing, it consists of a first part in letterpress where the author rigourously explains the theory of calligraphy, and a second part illustrated with masterfully engraved plates of examples (unfortunately, the scan does not do justice to the work of the engraver). His analysis of the various rules that govern the art of writing is very interesting and precious to calligraphers.

PAILLASSON (Charles), L’art d’écrire réduit à des démonstrations vraies et faciles…, 1760.

Paillasson was one of Rossignol’s most brilliant students. Because he spent a lot of time studying the works of his predecessors, he was probably one of the most knowledgeable writing masters in France in the second part of the 18th century. The authors of the Encyclopédie naturally asked him to write the article about “l’art d’écrire”. This is only an extract, the full version translated into Italian can be seen here. A text transcription of the French article can be found here, illustrations included. The plates were also published in Jean Henri Prosper Pouget’s book listed below. Although Paillasson knew a lot about the theory of writing, some masters judged that his style lacked the freedom of movement that gives a “soul” to the best examples of calligraphy.

ROLLET (E.), 18th century calligraphy, c.1761. (added July 2020)

This is a very interesting piece : this manuscript contains copies of various French copybooks, made by an amateur calligrapher. It will surely make you feel better about your own attemps at copying the Master penmen’s works.

ROYLLET [ROILLET] (Sébastien), Les fidèles tableaux de l’art d’écrire par colonnes de démonstrations…, 1764.

In this book, Royllet shows again his talent for analysing every little aspect of writing. Unfortunately, the person who scanned this book for Google didn’t open the biggest plate…

ROLAND (André-François), Principes démontrés des différentes écritures les plus usitées, 1766.

POUGET (Jean Henri Prosper), Dictionnaire de chiffres et de lettres ornées…, 1767.

Pouget worked as an artist working in the field of jewelry. This book is a manual explaining how to draw monograms. It includes the plates from Paillasson’s Art of writing article in the Encyclopédie as well as many examples of monograms and decorative ornaments that can be added to these cyphers.

BEDIGIS (Fançois Nicolas), L’Art d’écrire démontré par des principes approfondis…, 1768. (alt. copy)

Bédigis was a skilled penman and a teacher at the French Academy of Writing, this is his most interesting publication. Like Paillasson and Royllet, he cared about understanding and explaining the underlying rules of the art, which he considered specially important because the Coulée was becoming the predominant script in France and he felt that scribes cared more about writing fast than about writing well. His models of the French running hand (Coulée) are among the most beautiful ever printed. The examples of the English Round Hand in this book are also very beautiful. This volume is followed by a copy of J. Dartiguenave’s Tecnographie from 1818.

ROSSIGNOL (Louis), Nouveau livre d’ecriture d’après les meilleures exemples de Rossignol, 1770. (added July 2020)

This is a post-mortem publication of Rossignol’s works. The quality of engraving is not the best.

LAURENT (Gabriel), Lettres sur l’Art d’écrire, ou recherche et réunion des principes de l’écriture…, 1776.

Gabriel Laurent was responsible for a reform of the Ronde, only two plates illustrate his book.

ROYLLET (Sébastien) & BEDIGIS (François Nicolas), Démonstrations de l’art d’écrire par M. Royllet de l’académie royale d’écriture,…, 1785.

This book published by Bédigis, is a collection of plates written by his teacher, Royllet, with an introduction written by himself.

DEFARGUES (J.H), Traité de l’écriture sur l’enseignement ou Nouvelle méthode plus claire, 1787.

Detailed analysis of the structure of the Italienne Batarde, instructions and models.

SAINTOMER (Louis Antoine, l’ainé), Traité des vrais principes de l’écriture, 1787.

Saintomer was a very successful writing teacher, who essentially instructed merchants. Even though he had a very high opinion of himself, he was not as talented as his reputation would suggest, but he was a very good teacher. He took part in the Revolution of 1789 and penned a copy of the “Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen“. Saintomer published many books, a later edition of this one can be seen here (pages missing).

SAINTOMER (Louis-Antoine l’ainé), L’Ecriture démontrée, c.1789. (alt. copy)

SAINTOMER (Louis Antoine l’ainé), Abrégé des principes de l’écriture par Saintomer l’ainé, c.1790.

Detailed and illustrated instructions on how to write.

JUMEL (l’ainé), Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen décrétés par l’Assemblée nationale, rédigés pour l’instruction de la jeunesse, 1790.

The articles of the Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen, published by a writing master as models to be used in schools.

GUILLAUME-MONTFORT (Etienne), L’écriture démontrée…, 1797.

Another skilled penman, Roland’s pupil, occasionnally compared to Rossignol, he was a member of the Academy of Writing and great rival of Saintomer. His work and publications were inspired by d’Autrèpe (op. cit.). Another version of the title page can be seen here.

GUILLAUME-MONTFORT (Etienne), Traité élémentaire de l’art d’écrire où l’on a mis en exemple…, 1798.

This is Guillaume-Montfort’s major copybook. Like most French publications on the art, it contains a few letterpressed pages dedicated to the theory, followed by plates of illustration. It is an interesting publication, that perpetuated the transmission of the traditions linked to the profession of Maitre Ecrivain.

LECHARD (Charles), Production de tous les genres d’écriture basée sur des principes certains avec des traits d’ornement, 1798 (extract).

Lechard was a teacher of handwriting, this os just one of the many books he published, unfortunately we can’t see much.

TRESSE (l’aîné), Fables moralisées en quatrins, 18th century.

According to the title page, Tresse was a teacher of writing and mathematic in Paris. This book includes drills and basic principles as well as writing models. Another of his copybooks is listed (c.1820) in the next page.

Collection of French writing masters’ plates, c. 1725-1779.

This is a collection of many French copybook plates, some I haven’t seen in other books referenced here. The masters’ names include : Rossignol, Le Boeuf, Alais, Duval, Lesgret, Barbedor, Liverloz, Roland, Senault, Paillasson. The original books were published in the 17th and 18th century. One page from the Universal Penman, by Champion.

Dutch Republic

PALAIRET (Elie), La nouvelle méthode pour apprendre à bien écrire…, 1716.

This interesting manuel was written in French by a Dutch writing teacher. It consists of thorough explanations on all things connected to handwriting, especially when it comes to instructing children. If you understand French, you may find some useful information in there. A few plates illustrate the manual (better images here) : one plate shows a good example of the way letters should be spaced when writing the (French) Round hand (but the idea is similar to our “copperplate”) and some interesting offhand animals with numbered strokes.

PAS (Jan), Mathematische of wiskundige behandeling der schrijfkonst…, 1737.

This book was written in Dutch and in French and consists of a mathematical demonstration of writing principles. It is not precisely a copybook but it shows in detail how to draw each letter in Roman capitals and lowercase (based on typographic models), italic romans, French bastard and some gothic hands, including Dutch ornate capitals. Numbers ar not forgotten… This is going to be especially useful to hand letterers.

BAERS (Jan), Kabinet der Schrijfskonst, 1761.

Baers’ style is a continuation of Perling’s, the book contains a lot of models.

Manuscripts from various sources : 17th-19th century.

This collection of manuscripts from various Dutch calligraphers includes examples of Dutch and French hands.

Italy

TRONTE (Gennaro), Nuovo libro di caratteri, ovuero, L’arte d’imparare a bene scrivere, c.1780. (added July 2020)

Not the prettiest models of calligraphy…

POLANZANI (Francesco), La Penna da Scrivere, 1783.

Polanzani was a reputable Italian engraver. The book shows examples of a cursive script close to the French Batarde.

BERTOLOTTI (Francesco), L’arte dello scrivere, 1790.

DI PIETRO (Marco), Saggio di caratteri di moderno gusto, 1794.

Contains examples of the English round hand.

FROSINI (Giovacchino), Nuovo metodo e regole performare un bel carattere all’uso moderno, 1797.

Examples of a hand inspired from the French Ronde and Batarde, that was quite frequent in early 19th century italian copybooks.

Spain and Portugal

AZNAR DE POLANCO (Juan Claudio), Arte nuevo de escribir, 1719.

Plenty of commentary and a few plates showing the Spanish hands and a few others.

FIGUEIREDO (Manoel de Andrade de), Nova escola para aprender a ler, escrever, & contar…, 1722.

Figueiredo’s work follows the style of the great Italian masters in its use of clubbed ascenders and descenders, and of the spanish Diaz Morante in its very elaborate ornamental flourishes. This copybook includes a treatise explaining his theories and plates illustrating the local version of “round hand”, with some original variations.

SANTIAGO PALOMARES (Francisco Javier), Arte nueva de escribir, 1776.

Palomares was a paleographer and pioneer in the study of Spanish historical hands, he was concerned by the decline of Spanish calligraphy and, with his book, instituted a revival in the art of fine writing. This book was inspired by the works of Pedro Diaz Morante (17th century) and contains comments about what Palomares thought of his techniques, and how his own calligraphy grew from Diaz Morante’s style.

SERVIDORI (Domingo Maria de), Reflexiones sobre la verdadera arte de escribir por el Abate…, 1789.

Servidori set aside the teachings of Morante and Palomares in favor the English Round Hand, which he preferred. In his informed opinion, the English writing masters had best succeeded in developing a hand that was both beautiful and practical. He admired the works of Snell and Shelley in particular. However, his book is not just focusing on the English Round Hand but on almost all the hands published in european copybooks since the 1500’s. All the plates are in the second volume. It is a wonderful resource for anyone interested in the development of calligraphy after the invention of the printing press : lots of samples copied from the greatest masters.

ARAUJO (Jacintho de), Nova arte de escrever…, 1794.

This copybook focuses on analyzing and demonstrating the principles of a style close to the English Round Hand (some plates are reminiscent of Shelley’s Natural Writing), and even closer to today’s Engrosser’s script. The models of capital letters are still very influenced by the Italian Hand and the works of Dutch masters, with some very peculiar looking variations. Some very complex ornamentation (cadels) is present in the margins, the hand itself is kept quite simple.

Germany, Austria & Switzerland

Contrary to France and Spain, Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire did not adopt the English Round Hand and continued their own tradition based on gothic scripts. However, the copybooks below show that the English hand was marginally known and studied by writing masters.

WASER (Anna and her sisters, Elisabeth and Anna Maria), Schreibüebung…, 1708 (Zürich)

This one of few copybooks published by women, and in this case it was a family affair ! Anna was a Swiss painter and engraver, and she is responsible for the beautiful engraving of this copybook. Her sisters did most of the writing, but if you look at the signatures you’ll notice they all contributed with pen and ink. This short book of exemplars displays models of gothic and “italian” writing styles : Fraktur, Kurrent, Roman capitals, Gothic initials, and a page of Italian Bastarda.

(Multiple authors), Scrapbook of models, possibly assembled for use by a writing master (Nuremberg ?), 1709.

Paritius, Georg Heinrich, 1675-1725 : German calligraphic display initials. [Nuremberg?, s.n., ca. 1700] ; Spiegel der Schreib-Kunst / von Berthold Ulrich Hofmann. [Nuremberg] : In Verlegung Joh. Christoph Weigels, [after 1703] ; Der Blhenden Jugend : Neue Anleitung zur teutschen Fractur Lankelen und Corrent Schrifft. Nürnberg : In Verlegung Johann Christoph Weigels, [after 1703] ; Lucidissimum artis scriptoriae speculum. [Nuremberg] : Joh. Christoph Weigel excudit Noribergae, n.d. ; Regensburgische Schreib-Schule / Georg Heinrich Paritius. [Regensburg : s.n.], a[nn]o 1710 ; Grn̈dliche Anweisung zur Schreib-Kunst / Georg Heinrich Paritius. [Regensburg] : Verlegt von Joh. Christoph Weigeln, anno 1709. With some pages by Jan van de Velde and Dutch masters…

ANON, Manuscript, 1709.

This manuscript is kept in a French library, which means it could have been made in France. Written in German Kurrentschrift.

CRON, Herleitung der Current-Schrift, 1700.

This book focuses mainly on the kurrent-Schrift, giving examples of lowercases, capitals of various sizes and complexity and of course some ornamentation.

BAÜRENFEIND (Michael), Vollkommene Wiederherstellung der bißher sehr in Verfall…, 1716.

Examples of the Kurrent and other hands used in the German-speaking countries, including beautiful Fraktur examplars, as well as some examples of italian and French hands.

BAURENFEIND (Michael), Der zierlichen Schreib-Kunst…, 1716.

This copybook shows the German hands (Kurrent and Fraktur) in great detail, as well as foreign models, including several variations of the Cancellaresca, the French hands. The second part seems to be giving plenty of technical explanations. Plates illustrating how to cut the quill, draw flourishes and ornate gothic capitals (deconstruction of the different steps) and more models of various writing styles (many plates seem to be copies of foreign copybooks). The third part is another German copybook, by a J.G. VOGEL.

GEISSLER (Johann Friedrich Wilhelm), Nouveau livre d’écriture françoise, 1720.

This book was written by the secretary to a German prince, but it deals with the major French hands. The style is very simple, with very few decorative strokes. Even though Geissler’s hand is not as subtle as the best French masters’, it is interesting to see pages where the writing is the main object of attention.

TOCHTERMANN (Hieronymus), Pemanship exemplar, 1736.

Manuscript and in color

STAPSENS (Johann), Schul Vorschriften Johann Stäpsens, 1743.

This copybook covers the kurrent schrift and some older-looking round hands.

STÄPS (Johann Friedrich), Der getreue Schreibemeister, 1749. (added July 2020)

VICUM (Johann Friedrich), Selbstlehrende canzleymässige Dressdnische Schreibe-Schule, 1755.

VICUM (Johann Friedrich), Der getreue Schreibemeister, 1758. (added July 2020)

SCHIRNER (Johann), Schreibschule oder Deutsche, Lateinische und Franzosische Vorschriften, 1760. (extract)

The few pages available show some unpolished Bastard hand (French ?), and a few better looking gothic capitals. One page shows examples of drills close to those we do today.

TOCHTERMANN (Tobias), Kurtzverfasste Anweisung zu den Lateinischen Schrifften, 1765. (added July 2020)

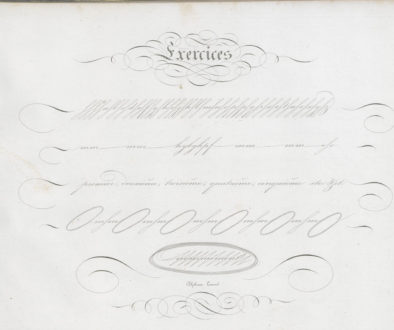

MATHEY (Joseph Aloyse), Exercices dans l’écriture française…, 1770.

This book about the French Ronde and Batarde is closer to the French copybooks from the 17th century. I couldn’t find any information on Mathey, but the title page hints that he was of German origins (from one of the principalities ?).

DEMOSER (Georg), Tirolische Schönschreibekunst, 1774.

ANON, Kurtze und gründliche Anweisung, nach der neuesten Art zierlich, zu Schreiben, 1775.

This copybook tackles the Current-Schrift as well as all the main european “round hands”. The author managed to imitate the works of French, Dutch, Italian and English masters quite well…

WEBER (Johann Gottfried), Allgemeine Anweisung der neuesten Schönschreibkunst…, 1780.

MERKEN (Johann), Liber artificiosus alphabeti maioris, c.1782.

A copybook done by someone who liked ornamentation a lot. It looks like it was also meant as a manual for drawing. The models are for German hands and French hands.

WESSEL (Johan Wilhelm), Sammlung kleiner Vorschriften zum Gebrauch für Lernende, 1790’s.

Examples of calligraphy in the English style followed by examples in Kurrent schrift. Some of the models mix the two styles in a way I haven’t seen elsewhere. The inspiration is certainly drawn from English copybooks.

BRAUN (Johann), Deutsche und Französische Vorschriften, 1793. (added July 2020)

Contains nice examples of german and French writing styles.

PIXIS (Johann Friederich), Vollständiger Unterricht der Schönschreibkunst für die Kurpfälzische, 1795. (added July 2020)

GRUNING (Andreas), Andreas Grüning’s Uebungen im Schönschreiben, 1797.

This is a German copybook focused on the end of century English round hand (looks a lot like our Engrosser’s Script), sadly it does not include special characters specific to German languages. The explanation might be that ERH is used in Germany as a “latin” script, still specifically meant to write in the languages that have adopted “latin” scripts.

RIEDELL (Carl Traugott), Neueste Schreibekunst, oder, Anweisung deutsche u. französische Handschriften…, 1799.

This coopybook focuses on the Current-Schrift. A few pages are devoted to the French Batarde and Coulée, but Riedell’s hand seems to have been more at ease with gothicized scripts than with round hands.

Kurtze und gründliche Anweisung, nach der neuesten Art zierlich, zu Schreiben.

A compendium of various exemplars that appeared in other books, including two plates signed by John Bland. Contains Kurrent, Fraktur, English round hand, Italienne Batarde and “Dutch round hand” (Dutch version of the French Italienne Batarde).

Sweden

BECKMAN (Carl), Grunderne Til Skrif-konsten, 1794.

An interesting book, containing a preface expalining the art of writing in Swedish. The plates seem to be directly inspired by French copybooks of this period. Models of French, English, German cursives.

Dear Sybille,

Thank you so much for putting all this information together. I am a beginner, I started practicing Copperplate (English Roundhand) last month. I also love history and researching, so I found your website yesterday and I am having so much fun looking at the old books you have on Flickr!

Your catalogue is amazing! Thank you and cheers from Brazil,

Shendel

Hi Shendel,

Thank you so much for your kind comment! I’m really happy that the research is useful to beginners and advanced calligraphers alike. There are so many hidden treasures out there, I’m just doing my best to uncover the ones I think can help, and to make them usable for modern clligraphers 😉

Xin chào bạn,tôi cảm ơn bạn vì rất nhiều thông tin bổ ích,tôi không thể đăng kí được Flickr để xem sách

Hello, I don’t think it is necessary to register to see the photos on Flickr. I’ve tried the links just now and had no problem. What book did you want to look at? I’m using the Brave browser. Maybe the problem you have has to do with cookies or ads?

Hello Sybille — great articles about the history of calligraphy. It’s been very helpful to read what was going on with this craft each century. Do you know anything about Angela Baroni? I am currently researching about her and I know she was a letter engraver, daughter of Giovanni Battista Baroni, but could not tell if she was also a calligrapher and I’m trying to find out…

Hi Luis, Thank you! I’m sorry, I didn’t know of her before your message. A quick Google search and the info I get is that she specialized in letter engraving (like you know)… For me, this means she must have had deep knowledge about letterforms and the different styles of writing she would engrave. She may not have been a calligrapher, but she knew how to draw the letters. Even though some engravers were able to engrave directly on the plate (in reverse), the process of engraving was faster and easier when the writing had been transferred onto the plate… Read more »

That’s a very interesting point your are putting there. She was the first woman to ever engrave a map, which is outstanding. I will let you know about further findings about her if you are interested 🙂

Thank you! I didn’t know that, this is fascinating! Map engraving was actually the start of letter engraving: this is how engravers practiced the engraving of the Cancellaresca (back in the 16th century), which allowed them to gain more expertise in letter engraving.

Dear Sybille, thanks so much for adding recently also more copybooks with examples containing German Kurrent script! So much to research :). For me, the shift from using broad nibs to pointed nibs in these styles is so interesting and now I have so many more examples to analyse!

Hello Stefanie!

I agree, the analysis of these books is fascinating! I must admit that I have not been searching a lot through German and Austrian Libraries’ treasures, so I have fewer of these examples. Don’t hesitate to tell me if you find books that you think should be added to the lists 😉

I can absolutely understand, the Kurrent script is a bit weird and some of the books also are not top-notch ;D … but I have a deep interest in different sorts of Gothic handwriting styles, also the English and French versions, and so I am happy to find here more and more :). I do have some books and faksimiles I will digitize when I find time – I’ll let you know, so if you like you can add them! Also regarding your comment about Andreas Grüning’s book, with the English exemplars – I think there are no letters like… Read more »

Thank you for the explanation! I hadn’t noticed… I browse most of these books much too fast to notice such things. Germans did indeed abandon their national “writing / graphic identity” much later than neighbouring countries. It made sense to them that words in foreign languages should be written in the corresponding writing style. It’s also a way of protecting your own vocabulary from invasion by foreign words… I think it’s kind of clever.

Haha, very welcome. I think it also had to do with a certain showing-off of education … that you knew how to say (and write) certain words in French or Latin. I think a lot plays into that … Also, other than France or Spain who were states early on with a distinct capital, Germany was for many centuries a collection of many, some of them very small kingdoms and language and script maybe was insofar a strong thing for self-identification …

Very good point! I hadn’t thought of it that way! Belgium didn’t exist until 1830, but I think our national identity partially hinges on our humour about our lack of self-identification… I should look into this!

Oh I didn’t know that! Never stop learning I guess :). Thanks again for collecting all these great ressources and your thoughts about all these!

This is a wonderful site! You have done a great job of tracking down online copies of writing manuals. Fortunately, I live in Chicago and can consult originals at the Newberry Library.

August 2024/ This is a wonderful compilation of references (say THAT 10 times fast). I think the 1500s / 1600s is an inspiring time, where the Italian hands met the Germanic – you get these great mashups of small blackletter minuscules and swingy Italian caps – woo! You do a good job of describing how the center(s) of lettering moved from country to country, which often paralleled the economic shifts I suppose. Thank you from a signpainter – I’m always thinking about how these letters would be done with a brush.

Hi Lee,

Thank you so much for your kind words. It makes me happy to know this content is valuable to you (and to know you’re a signpainter)! Handwriting was such a valuable tool that its evolution was naturally tied to all the evolutions in human society, be it art, economy, politics… Looking back now, I feel like it should probably have evolved more than it has since the 19th century. But then, we now have computers and smartphones that in themselves change our relationship to the written word.

Hi. I’m an author of historical fiction. I’m trying to find out if hand-writing experts were available in England in the late 18th century to give evidence at trials. I’m not talking about those who might have analysed writing for personality traits, but rather experts about who might have written a particular document. I’d be surprised if none existed since forgery was a capital offence at the time. Perhaps some of the copybook makers included people who would turn up at court and give evidence. When researching for my last book, ‘Easter At Netherfield’, I came across a case in… Read more »