16th century : the rise of the writing master

The invention of printing in the middle of the 15th century had a dramatic impact on the way books were produced and consumed, and – by association – on the role that scribes played in society. While printing quickly became the prevalent method by which books were produced, the documents used in business, legal and financial transactions continued to be handwritten… As the medieval scribe disappeared, the economic and social context of the Renaissance – starting in Italy – allowed teachers of handwriting (writing masters) to massively emerge, and the invention of printing allowed those men to publish manuals that would help students in the practice of writing.

These “copy-books” not only served as models to copy from, but also served to publicize the work of the masters and guarantee their reputations well beyond the frontiers of their respective cities and countries. Italy was the precursor in this field (as in many others), the cancellareca (italic / chancery hand) and the more cursive “italian hand” quickly seduced scribes… Arrighi, Tagliente, Palatino and Cresci’s books influenced the development of handwriting all over western Europe, and their success inspired many writing masters up until the 20th century.

The first writing copy-books were all printed from woodcut plates. The method gave acceptable results, but writing masters knew that they couldn’t rely on the engraver to reproduce finer details. Their designs had to stay relatively simple, and their copy-books only conveyed the basic principles of the various writing styles represented.

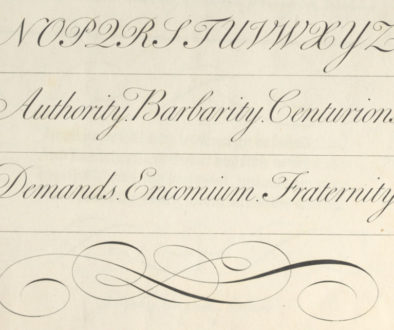

However, engravers were finally able to reproduce good letterforms on copper-plates around 1570, and the copy-books themselves began to change. The results were stunning : the subtle contrasts of the printed letterforms were enhanced by the new method of engraving, it gave a crisper image and allowed to reproduce small examples of the script as well as elaborate flourishings known as ‘command of hand’. From then on, writing-masters wouldn’t have to just focus on giving basic instructions on writing in their books, they would be able to design and publish the most elaborate artworks… as long as a good letter engraver was around.

Italy

FANTI (Sigismondo), Theorica et pratica de modo scribendi…, 1514.

Fanti was an Italian architect, astrologer, mathematician, and writing-master. This publication was the first illustrated manual on the art of writing, and the first book illustrated with calligraphic models of the alphabet (Roman caps). It provided practical advice on selecting implements, making ink, on the correct way of holding the pen, and on spacing letters.

ARRIGHI (Ludivico Vincentino, degli), La Operina, 1522. (Better images, harder to browse copy)

The first writing manual on Cancellaresca (Italic script). Arrighi was a writer of briefs in the Papal Chancery where the new cursive hand had been developed, he turned to printing (and teaching) after losing his job. If you’d like to see some of his original work, the Spanish National Library digitized a manuscript of Petrarch’s works by the hand of the Italian master.

ARRIGHI (Ludivico Vincentino, degli), Il modo de temperare le penne…, 1523.

A second book by Arrighi, explaining the way to prepare and cut the quill, as well as illustrating various writing styles. This part bound with La Operina, in the copy linked above.

TAGLIENTE (Giovanni Antonio), Lo presente libro insegna la vera arte de lo excellente scriuere…, 1524. (Better images, harder to browse copy)

Tagliente was a teacher of handwriting in the Venetian chancery, his book was published shortly after Arrighi’s La Operina, and was his most influential manual (at least 30 editions were published in that century alone !). The plates display a less stilted style of chancery, but bear in mind that not everything was handwritten : some of the pages were printed from types cut to resemble his script.

DA CARPI (Ugo), Thesauro de scrittori, 1535.

Ugo Da Carpi was a Roman printmaker, known for his works in woodblock printing. He had engraved Arrighi’s Operina and later printed his own version including the second part Il modo…

This book is described as an anthology of foereign alphabets, “extracted from celebrated authors”, including Fanti, Arrighi and Tagliente. There were various editions of this book, not all containing the same models.

PALATINO (Giovanbattista), Libro nuovo d’imprare a scrivere tutte sorte lettere antiche et moderne, 1540.

With this book, Palatino intended to appeal to a wider audience than his predecessors (Arrighi and Tagliente) : his plates not only show his own version of the chancery but also include samples of many other hands in use in Italy at the time. The second part of the book deals with cryptography and the third demonstrates unusual alphabets. The link will take you to a later edition of the book titled Compendio del Gran Volume de l’arte bene et liggidramente scrivere (1566). Several manuscripts in the hand of Palatino survive (At the Bodleian).

AMPHIAREO DA FERRARA (Vespasiano ), Opera di frate Vespasiano Amphiareo da Ferrara dell’ordine minore conventvale, nella qvale s’insegna a scrivere varie sorti di lettere, 1572.

According to Joyce Irene Whalley, Amphiareo’s work is important in the development of the chancery cursive script : his use of loops and joins more common in mercantile scripts helped to produce a more speedy hand. This book was first published under the title Uno novo modo d’insegnar a scrivere in 1548.

CRESCI (Francesco), Essemplare di piu sorti lettere, 1560.

Cresci introduced a different type of Cancellaresca after criticizing the models of Palatino for being too slow to perform. His own models proposed a speedier, more practical hand for correspondence and book-keeping. One of the most visible changes to the chancery italic was the introduction of “clubbed” ascenders, made with a looped circular movement that produced a blobbed top. This book is where the “Italian hand” practiced today finds its roots. Cresci’s work was extremely influential and shaped the evolution of handwriting in Europe until the beginning of the 20th century.

SIENA (Don Agustino da), Opera del reverendo padre don Avgvstino da Sciena, monaco certosino : nellaquale s’insegna a scriuere varie sorti di lettere, 1565.

Printed in Venice. Agustino Da Siena was a priest and his intention was to provide instruction in writing to young people who wouldn’t have otherwise have had access to a private teacher. His Cancellaresca is influenced by Palatino and Tagliente. He dedicates a whole section of the book to the mercantile hand (hand used by the merchants), informing the reader that it is faster than the Chancery cursive and widely used in Venice.

PALATINO (Giovanbattista), Compendio del Gran Volume, 1566.

The response of Palatino to Cresci’s insults… This is a reissue of the Libro nuovo with a new introduction in which he harshly criticizes Cresci’s arrogance. The plates with chancery models were re-engraved with many of Creci’s innovations.

ALDROVANI (Ulisse), Manuscript in italian hand, c.1560-1600 ? (added september 2020)

A beautiful manuscript written in an italian hand style close to Cresci’s. These handwritten pages are a beautiful example of the use of the hand “in real life”, the imperfections and variations of slant and form give life to the hand.

CRESCI (Francesco), Il Perfetto Scrittore, 1570.

Cresci’s second book, containing more illustrations of his modern Cancellaresca. This is a copy of the first edition, containing copies of a knotted alphabet of capitals printed from copperplates engraved by Andrea Marelli (at the end of the book). While the first part of the book was being carved in woodplates, Cresci realized the potential of copper engraving, which was being introduced for the reproduction of illustrations, and he designed the alphabet as an addition to his book. More info on this subject here.

HERCOLANI (Giulantonio), Lo Scritor’ Utile, 1574.

Hercolani’s works were among the first to be printed from copperplate engravings. This book is Hercolani’s second publication, a reprint of his first book. Comparing the plates with the copybooks mentioned above, you will be able to get a better idea of the freedom conferred on the scribe by this new method of reproduction.

SCALZINI (Marcello, “Il Camerino”), Varie e diverse maniere di lettere cancelleresche, correnti, formate et formatelle, c. 1575.

A manuscript copybook kept in the Vatican Library. This was judged “a mediocre performance” by James Wardrop (who participated in the revival of the Chancery in England). I will note that Scalzini was just 19 at the time. In any case, this gives us an opportunity to see the difference between handwritten and engraved models.

DA MONTE REGALE (Conretto), Vn novo et facil modo d’imparar’ a scriuere, 1576.

Conretto was a writing master and teacher of arithmetic and geometry. His models are similar to Cresci’s, but he was less talented.

CRESCI (Francesco), Il Perfetto Cancellaresco Corsivo, 1579.

The third part of Cresci’s works. No fancy borders this time, but some very cursive examples of his “cancellaresca moderna”.

SCALZINI (Marcello, “Il Camerino”), Il Secretario…, 1581.

Most of the book deals with the Cancellaresca Corsiva developed in the Papal chancery, with a special emphasis on the need for speed. It also displays some examples of big flourished decorations, made possible by the new printing technique.

CURIONE (Ludovico), Il Cancelliere…, 1582.

Curione was with Scalzini, seen as a rival of Cresci (although he was Cresci’s pupil). Their works were the most important contemporary influences in Italy, the Netherlands and in France, in the last two decades of the 16th century. In this book printed from engraved copperplates, you will see some beautiful examples of the cursive chancery hand. Curione published his 4 books in a weird order, he had them all ready in 1582 but probably couldn’t afford all publications at once. This is n°4 (see title page).

GAGLIARDELLI (Salvadore), Soprascritte, 1583.

Gagliardelli was a pupil of Cresci. This is a guide to the correct way of addressing correspondence : using the correct abbreviations and wording was important. Adding a few flourishes on the address was a way of attracting the addresse’s attention. Each of the ‘soprascritte’ (267 of them !) is written using the Chancery cursive. This book shows the degreee of specialization some scribes developped at the time, clearly Gagliardelli paid a lot of attention to ‘first impressions’.

VEROVIO (Simone), Essemplare di XIIII lingue principalissime, 1587.

Simone Verovio originated in the XVII provinces (now Netherlands and Belgium), and had come to Rome to flee war and find success. He was a papal chancery scribe who also had a print shop and edited books of music and writing books. The engraving was done by Martin Van Buyten (a fellow Dutch), who was one of the best letter engravers (in copper) of his time. Like many of his compatriots, he went to Italy where he engraved for several great masters such as Curione. This is a single sheet showing various styles of writing in 14 languages. The printer, Nicolas van Aelst (also named on the plate) was also of Dutch origins, exiled in Italy. Both worked in Rome.

VEROVIO (Simone), Il Primo Libro Delli Essempi, 1587.

This is one of Verovio’s writing books. It contains sample sentences for use in letters and other written communication. All plates are written in the cursive chancery inspired by Cresci’s innovations, includes some flourished ornamentation. Engraving by Martin Van Buyten.

CURIONE (Ludovico), La notomia delle cancellaresche corsiue, & altre maniere di lettere, 1588.

Most of the plates are devoted to the chancery hand, including “lettera corsiva” variant, and “Lettre que escriuent les dames de France”. Curione published his 4 books in a weird order, he had them all ready in 1582 but probably couldn’t afford all publications at once. This is n°2 (see title page).

ROMANO (Giacomo), Il primo libro di scrivere di Iacomo Romano…, 1589.

Another pupil of Cresci. This book is shaped in a similar pattern to Cresci’s Il Perfetto Scrittore and his models are very close to his master’s.

CURIONE (Ludovico), Folder with loose pages, with no title page…, 1593. (added March 2021)

Examples of the work of Curione, including a page of manuscript italian hand, although this may not be by the master himself.

CURIONE (Ludovico), Il teatro delle cancellaresche, 1593. (additional pages)

N°3 of Curione’s 4 books, and the last to be published.

FRANCO (Giacomo), Il Franco modo di scrivere Cancellaresco moderno…, 1595.

SCIPIONE (Leone), Examples of the Chancery hand, 1598.

Typical examples of the “Italian hand” in the style of Cresci.

BLANCO (Cristoforo), several broadsides, 1598. One – Two – Three – Four

These are large sheets of paper printed on one side, use as specimen sheets showing various writing hands. In this case, the Chancery hand is dominant. Cristoforo Blanco was a letter engraver working in Rome. These sheets may have been used to show sample of his work.

Various works at the Newberry Library, Calligraphy samples for the study of Italian paleography, 15th-17th century.

On this page, you will find a series of handwritten books filled with samples of calligraphy. All are interesting in their own way, some look more professional than others. This collection shows the evolution of the Chancery in Italy during the Renaissance and Early Modern period.

Spain

ICIAR (Juan, de), Recopilacion subtilissima : intutilada Orthographia practica…, 1548.

Iciar (or Yciar) likely spent some time in Italy before writing this book : he drew inspiration from Palatino’s work and may have studied with him. The plates in this book were beautifully engraved but Iciar’s work had little influence in Spain and was eclipsed by Francisco Lucas’s publications (circa 1580).

ICIAR (Juan, de), Arte subtilissima, por la qual se enseña a escreuir perfectamente…, 1553.

This is a second, enlarged edition of Iciar’s previous title. Both books contain some remarkable examples of white on black printing, with beautiful ornaments and illustration.

LUCAS (Francisco), Arte de escrivir…, 1571.

The link will take you to a reprint from 1608, which seems to be the last reprint. Lucas’ work was specially significant in the development of two major Spanish hands : the Bastarda and the Redondilla, which remained in use in Spain for several centuries. The Redondilla was a combination of the italian chancery and local mercantile hands while the Bastarda was a cursive version of the Redondilla.

ORFEI (Luca), Varie inscrittioni del santiss. S.N. Sixto V pont. max. da Lvca Horfei…, 1590.

This seems to be copies of inscriptions in Romans. There are also examples of the Italian hand.

France

HAMON (Pierre), Recueil d’alphabets et d’exemples d’écritures anciennes, 1566.

(Manuscript)

HAMON (Pierre), Alphabet de Plusieurs sortes de lettres, 1567.

Pierre Hamon attempted to collect as many old and contemporary writing models as possible in this book. Some styles are very odd and not very practical… It has been recently established that this is the first known copybook to have been printed from copperplates.

DE LA RUE (Jacques), Exemplaires de plusieurs sortes de lettres, 1569. & Alphabet de dissemblables sortes de lettres italiques…, 1565

Both books are bound in one volume. They provide examples of the different hands used in France at the time, including the French gothic handwriting (now called “lettre de civilité”) and some examples of “Italics” and “Italian” hands.

BEAUCHESNE, (Jean, de), Le Tresor d’escriture, auquel est contenu tout ce qui est requis & nécessaire à tous amateurs dudict art.., 1580.

Like some other French masters, Beauchesne was a Huguenot (a French protestant) who had to exile himself for religious reasons. This is his second publication, which was influenced by his travels in Italy. His first copybook (A booke containing divers sort of hands) had been published in London in 1571 with the help of John Baildon… and is known as the very first English copybook. A nice manuscript (different works) attributed to the same author can be found here. However, this manuscript is probably wrongly attributed.

BEAUCHESNE, (Jean de), Specimens of calligraphy, c.1610.

According to the note attached to this bound manuscript : This a copy-book that was written for Elizabeth of Bohemia, daughter of James I. Beauchesne, her writing master, proudly notes in his colophon that he was in his 73rd year when he wrote the book.

BEAULIEU, Exemplaires du Sieur Beaulieu : où sont monstrées fidellement toutes sortes de lettres et caracteres de finance…, 1599. (Alternative link)

Little is known about this master from Montpellier. Most of his book is dedicated to the French gothic hand, but a few beautiful plates show his specimens of “Italian hand”. The beautiful illustrations on the title page show the author’s erudition.

LE GAGNEUR (Guillaume), La Technographie ou brieve methode pour parvenir à la parfaite connoissance de l’ecriture françoyse ; La Rizographie ou les sources, elémens et perfecçions de l’ecriture italienne… ; La Caligraphie ou belle écriture de la lettre grecque, (Three books in one volume) 1599.

Le Gagneur was an extremely respected calligrapher, secretary to Henri III and Henri IV. These three books were beautifully engraved by Frisius (the best letter engraver of this period). The first book is dedicated to the French gothic, with a plate that shows the small letters in great detail ; the second book is dedicated to the italian hand, and the third to the greek letter. For each hand, he shows his penhold and many beautiful variations. (Other links : La Technographie ; La Rizographie ; )

Low Countries

MERCATOR (Gerard), Literarum latinarum, 1540.

Mercator was a renowned geographer and the founder of cartography school in (what is now known as) Belgium. He wrote this book of instructions on how to write the chancery script with cartographers in mind. It was the first of the genre in the region and only the third manual, chronologically, to deal with italic script.

SILVIUS (Willem), Variarum Scripturarum Exempla, c.1550.

A small manuscript copybook that served as Silvius’ personal writing book when he was a writing master in Louvain. He probably used it to attract customers. In 1562, Silvius was active as a printer in Antwerp, he requested and was granted a privilege allowing him to publish this work in print. However, no printed copies are known today, the project may have never been completed. This book contains a large array of writing styles, including all the hands useful in the Low Countries at the time… Mutliple hands in various languages, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Dutch, Latin, all written in the appropriate national hands, as well as samples in Hebrew and Greek.

PLANTIN (Christophe), ABC, ou Exemples propres pour apprendre les enfans à escrire..., 1568.

Plantin was a very successful printer in the Southern Low Countries (Antwerp) : he published many books on different subjects and had a talent to know which publications would appeal to the public. This book was aimed at children and young people who were learning to write. On each page, a decorated initial was printed, and the owner of the book would complete the page in his own writing. Such books were quite common in the Low Countries. The calligrapher responsible for the writing is unknown.

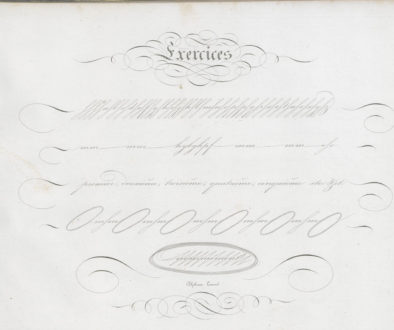

PERRET (Clement), Exercitatio alphabetica, 1569. (added July 2020)

Until recently, this was believed to be the first published copybook printed from engraved metal plates (intaglio), rather than from woodcuts. Clément Perret was a very young writing master from Brussels, Belgium. The book is very rare and stayed under the radar for a long time. It is possible that the Flemish engravers had gained expertise in the engraving of the chancery hand through engraving maps (map makers had been seduced by Mercator’s copybook). The engraver who worked on the book, Cornelis de Hooghe, was in fact renowned for his works in map engraving. The illustrated borders are particularly remarkable in this book.

HOUTHUSIUS (Jakob), Exemplaria Sive Formvlæ, 1591. (Link to another copy)

Another beautiful copybook. The structure and format are inspired by Perret’s Exercitatio, as is the title plate with its ornate border. It contains exemples of writing in multiple European languages and writing styles.

BOISSENS (Cornelis), Promptuarium variarum scripturarum…, 1594.

Cornelis Boissens collected calligraphy and art, he left useful comments on Dutch calligraphers from his time (this is the beginning of the Golden Age of Dutch calligraphy). He was opposed to the use of superfluous ornamentation in calligraphy – even though his book does not exactly reflect that, it is an example of ‘sober’ Dutch calligraphy. Boissens engraved his own books.

BOISSENS (Cornelis), Groote ende kleine capitalen tot dienst der penn’constlievende, c.1594-1610.

A small book of Gothic capitals.

HONDIUS (Jodocus), Theatrum Artis Scribendi, 1594. (Alternative link)

This succeful book was a collection of the greatest masters of the time : the English Bales and Billingsley, the Dutch Caspar Becq and his talented assistant Jan van de Velde, Maria Strick, and the works of the three winners of the Rotterdam Golden Quill contest of 1590 (Van Sambix, Hendrix and Velde). Hondius was better known for his work as a map engraver, his calligraphy was greatly inspired by Mercator and Perret.

England

BAILDON (John) & BEAUCHESNE (Jean de), A booke containing diverse sortes of hands, 1571.

This is the first big copybook of this kind published by an English master in England. Little is known about Baildon, Beauchesne was an exiled French Huguenot, who later published other copybooks in French. The French influence in the composition of the book is very clear (look at the French copybooks of this period). The plates show the various hands in use in England at the time, including the Secretary and court hand, ad well as Roman and italian hands inspired by the works of Cresci.

SCOTTOWE (John), Alphabet of ornamental capitals used as initials in specimen pages of calligraphy, 1592.

I don’t have any information about this calligrapher. This is a collection of manuscripts in a style very similar to what we find in Baildon and Beauchesne’s book.

Germany, Switzerland…

WYSS (Urban), Libellus valde doctus elegans, & vtilis, multa et varia scribendarum literarum genera complectens, 1549. (Switzerland)

Wyss’ work had a significant influence in northern Europe during the 16th century. Some of the woodcut illustrations used here were copied in later books and copybooks. The plates provide a good overview of all the contemporary and historical hands in use at the time, with a focus on “German” styles.

FUGGER (Wolfgang), Ein nutzlich vnd wolgegrundt Formular Manncherley schöner schriefften, 1553. (also at the Library of Congress)

Lots of explanations and examples of early Kurrents and German chancery hands, some beautiful Fraktur, Textura and Rotunda exemplars and an early flourishing systematic (for Fraktur capitals).

Fugger’s “Latin” scripts are not as well made as his Gothic hands. He was the most famous pupil of Johann Neudörffer.

NEUDORFFER (Johann), Ein gute Ordnung und kurtze unterricht der fürnemsten grunde…, 1555.

Neudörffer was the most influential writing master in Germany at his time. He was (among others) responsible for how Fraktur developed and wrote the inscriptions on Dürer’s apostle paintings. He was famous for his hands-on teaching – he already started with basic strokes and what we could call drills today, and then went on to letters. He did not use gudelines of any sort. “Ein Gute” is one of his major copybooks, but it contains no explanatory test. He published more in depth explanations in another book, Gesprechbüchlein, that was reissued by his grandson Anton, in 1601.

BOCSKAY (Georg), Mira calligraphiae monumenta, 1561. (Austria)

Bocskay was imperial secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, he created this book as a demonstration of his own pre-eminence among scribes. It is not a writing manual, and only exists as a manuscript, but it does include a wide variety of contemporary and historical scripts. Years later, Bocskay’s beautiful calligraphy was exquisitely illuminated by Joris Hoefnagel.

Geachte Mevrouw,

Ik hoop dat ik u een vraag mag stellen. Ik heb hulp nodig om bijgaand monogram te ontcijferen. Het staat op een 15e eeuws Vlaams schilderij, maar kan ook een 16e eeuwse toevoeging zijn. Ik zie duidelijk een J, maar is dat een o in de open ruimte of een s ? Ik hoop de geportretteerde te kunnen identificeren. Alvast vriendelijk dank,

Joris Loeff

Thank you for your comment, I hope it’s ok to reply in English as my Dutch is very far away 😉

The letter you identify as J does have the top of a J or I, but the bottom of an L, which is really weird. As for the second letter, it’s really hard to tell. I would say it looks closer to an O.

I’m sorry, this is probably not super helpful.. I’m sending you an email with the name of someone who might help.

All the best,

Sybille.

Thank you very much, I will ask the person you indicated.

Sincerely,

Joris

Great list, very helpful.

Do you have the list of 16C writing books in Osley Luminaro (1972)

I can send you the list if helpful,

would be nice to include Fanti (1514), and Torniello (1517) as they’re often overlooked.

Also interesting is the first writing book published in England

A Booke Containing Divers Sortes of Hands by Jean de Beauchesne and John Baildon (1570)

Hello Roland, Thank you for your useful comment ! I know there are a lot of other beautiful reference books that would belong in this list (and I know of Osley’s list 😉 )… My aim here was to link to books available online, which is why I had to limit the choices. I will definitely search for publications by Fanti and Torniello, it’s possible that they are now digitized and online. The problem is the same with Beauchesne and Baildon’s book. I think I mentionned it in one of my previous posts 😉 Thank you again for the great… Read more »

I would really love to get hold of the Jean de Beauchesne and John Baildon, but Fanti is here https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbc0001.2010rosen0770/?sp=1&st=gallery keep up the great work! x

Thank you for the link, saves me the time ! I’ll keep looking for Baildon and Beauchesne’s book, it would be great to add it to the list.

hi, I have scanned the Beauchesne and Baildon book and uploaded here:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/194522112@N07/albums/72157720193698418

Its a 1571 printing, Roland

Hello Roland ! Thank you so much for sharing this beautiful scan ! I’m adding the link to the list

I have photographed the expanded 1590 “New Edition” too, I’ll upload it next week 🙂

Thank you for this outstanding list of books and for your most helpful and incisive comments about each one. I’m a developmental psychologist at Michigan State University, and one of my interests is the development of the neural and social underpinnings of lateral (left-right) differences in skill acquisition, including learning to write. I’ve written previously on the history of this instruction, and books like the ones on this list will, I hope, tell me more about its beginnings in the form of copy-books and manuals on penmanship.

Thank you! Your research sounds extremely interesting! I can’t remember the sources exactly but I think there was no clear bias against left-handedness in copybooks before the 19th century. Of course, it may imply that using the right hand was obvious. One French master even encouraged the use of both hands: one of his sons had lost his right hand in an accident and had had to learn to write with the left hand (I think the master’s name is Bédigis, in the 18th century)… I’ll keep an eye out and let you know if I see anything that may… Read more »

[…] Ps – if you want a really cool website showing work from the 1500’s as well as the 1600’s https://pennavolans.com/16th-century-calligraphy/ […]

This is my go-to site for calligraphic guidance as I begin each piece of calligraphy. Thank you for creating and sharing all this!!

Thank you for your kind words, it makes me happy to know you find this website useful !

Dear Sybille,

Thanks very much for the work at _Penna Volans_. A very useful

and informative resource!!!

For a few days I’ve been trying to forage examples of works in

a similar hand as the beautiful, higly calligraphic, examples

as the writing at the back of the modern Filipo banknotes such

as [1]. I also haven’t been able to identify the name of the

hand, or what it’s based on.

Please keep up the good work.

Regards/Marc

[1]

Thank you Marc ! The style you’re referring to looks to me like the Zapfino font. It is a modern variation of Italics (cancellaresca) with some characteristics of Italian hand (cancellaresca moderna, Cresci’s invention, maybe Tagliente. Both authors can be found on this page). The font was created by Herman Zapf, look it up it’s really nice 😉